Jacksboro, Texas: Legendary Land of Soldiers, Cowboys, and Indians on the Violent Frontier

Jacksboro has lived up to its two "name sakes": brothers William and Patrick Jack, who twice attacked Mexican garrisons in Texas' revolt against Mexico. Both were slave holders and fought to maintain the institution in Texas. In fact, Colonel Juan Bradburn, Mexican commander of a fort being built to force the Texas planters to pay taxes on goods, imported and exported, lit a fuse under the resolve of the Texicans to maintain control over their slaves by taking a slave of one of the Jack brothers and putting him to work on the fort. When William B. Travis, attorney for the brothers, insisted that Bradburn release their property, Bradburn replied that the slave in question would be freed by the Mexican army. To this Travis objected and was promptly arrested. The Jack brothers, along with James Bowie, led the assault on the fort and the seizure of Colonel Bradburn. Only the fortuitous intervention of Stephen F. Austin, in the company of a Mexican officer who outranked Bradburn, kept the Texicans from "stringing up" the Kentuckian colonel serving in the Mexican army. Instead of being hanged by the angry Texicans, Bradburn was ordered back to Mexico by his superior officer.

Jack County, though named in honor of the Jack brothers who fought the Mexican army to maintain slavery, voted against secession in 1860. An intense belief in freedom for the individual, along with an innate desire to "make good" on the violent frontier, drove the first citizens of Jacksboro to brave attacks from Comanches and Kiowas who claimed the land as their own. Jack County men were rugged types. Inspector General of the Army, Randolph Marcy, who accompanied General William T. Sherman on an inspection of the frontier in 1871, observed of the Texans in the Jacksboro area," they expose women and children singly on the road and in cabins far off from others as if they were safe in Illinois. If the Comanches don't steal horses, it is because they can't be tempted." read more

Little did Marcy and Sherman know, as they rode from Fort Belknap near the present city of Graham to Fort Richardson just outside Jacksboro on an inspection tour of the frontier, that they passed underneath the hostile gaze of Kiowa and Comanche warriors who had left the Kiowa, Comanche, Apache Reservation without permission from the authorities at Fort Sill. The two generals' lives might well have ended if the Kiowa prophet Mamanti had not held the eager warriors back, though many were intent on attacking the generals and their small escort, who, with good luck, might have been able to defend the generals in their care. But it will never be known what might have happened because Mamanti dreamed the night before that the warriors should attack the second group of white men and let the first group pass unharmed.

Once he arrived at Fort Sill, Sherman learned that three Kiowa chiefs were openly bragging about killing seven of the twelve teamsters who followed Sherman and his escort on the road from Fort Belknap to Fort Richardson. Twelve men either drove the wagons or rode as escorts to the teamsters who made up the Warren Wagon Train hauling supplies from one fort to another. The twelve brave men never dreamed they would have to fight for their lives on the road that Marcy had laid out a few years before Jacksboro became a town. Four years before Sherman's and Marcy's inspection tour in 1871, the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, Kansas, had called for an end to the free-roaming ways of the Kiowas and Comanches. Newspapers in Kansas and Texas called on the government to defend settlers from Indian attacks. Their pleas for help resulted in a treaty that placed all Kiowas and Comanches on a three-million-acre reservation, with Fort Sill built to keep "hostiles" from leaving their open-air prison.

Whites who had called for the Indians to be removed as a threat to their possession of the former hunting lands of the southern Plains tribes were greatly relieved that the reservation had been formed and that the U.S. military was there to keep the Indians off the war path. From 1867 forward, no member of the Kiowa, Comanche or Kiowa-Apache tribes could legally leave the reservation without permission from authorities at Fort Sill. Telling men who had once ridden all the way to Central America and as far as their mounts and arms could take them that they could no longer make such trips was like delivering a death sentence to the proud warriors.

The eloquent and heart-felt pleadings of the Indians were given no consideration by government agents intent on achieving their true purpose in executing the Treaty of Medicine Lodge: to extract from the tribes the agreement not to attack "any person at home, or traveling , nor molest or disturb any wagon trains, coaches, mules, or cattle belonging to the people of the United States." The authors of the treaty concluded with its true purpose: "They (Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches) will never kill or scalp white men nor attempt to do them harm." What the Indians got in return for settling down on a small portion of their former range was hunger, despair, and a burning desire for revenge. General Marcy, unlike most of his peers in blue, viewed the Comanches as fellow human beings and not "savages." In 1866, one year before the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, Kansas, was forced on the Comanches and their allies, Marcy wrote, "The Comanche government is essentially patriarchal, guided by wise and fraternal councils. They are insensible to the wants and luxuries of civilization, and know neither poverty or riches, vice or virtue, and are alike exempt from the vicissitudes of fortune. Theirs is a happy state of social equality, which knows not the perplexities of political ambition or the crimes of avarice."

Yet Marcy, like all officers, regardless of their personal feelings, followed orders, even if he felt that the Indians were not properly respected in treaty negotiations. It is likely that Marcy listened intently to Comanche Chief Ten Bears' eloquent speech in opposition to the treaty. The chief was up in years and had been to Washington, D.C. and therefore knew of the power of the American government. The chief did put his mark on the treaty, but only after addressing the soldier chiefs as follows: "The Comanches are not weak and blind like the pups of a dog when only seven sleeps old. They are strong and far-sighted like grown horses. There are things you have said to me that I do not like. They are not sweet like sugar, but bitter like gourds. You said you wanted to put us on a reservation, to build us houses and make us Medicine Lodges. I do not want them. I was born upon the prairie where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun. I was born where there were no enclosures and where everything drew a free breath. I want to die there and not within walls." Though Marcy undoubtedly listened, government officials from the Departments of War and Interior got the treaty they desired with no regard for Ten Bear's feelings in the matter.

A decade before Texas entered the union as a state in 1845, descendants of Celtic warriors fought for land that was long held by Kiowas and Comanches, and their allies the Wichitas. The interlopers into Comancheria lost many battles, but won their share as well. Most cowboys from Jack County scalped the Indians they killed, with few retreating from the horror of frontier violence. Yet many were forced by Comanche and Kiowa warriors to abandon their burned-out cabins, some leaving behind fresh burials, while others grieved over the loss of their children to the Indians who raised them as their own. Marcy observed as he and Sherman passed burned out cabins and vacant fields that there were fewer people in the area than when he had laid out the road that passed through the site where Jacksboro was to be built twenty-two years earlier. Only the bravest and most determined men and women remained in Jack and adjoining counties.

Such people established Jacksboro on the banks of Lost Creek in 1855. According to the author's Aunt Myrtle Neeley Brewer in her journal about her youth in Jack County, her grandfather, John Wood, built the first cabin in Jack County "before there was a Jacksboro." Wood, like the majority of the population of Jacksboro and surrounding farms and ranches, was a descendant of Scottish and Irish warrior clans and fighters from the north of England. The very fact that the ancestors of Jack County's intrepid citizens had left all they had known in the old world to immigrate to North America meant that their descendants would also have the itch to move many times as they sought to find a better patch of land and water just over the horizon. Those who stayed in Jack County during the years from 1855 until the trial of the Kiowa chiefs in 1871 were the hardiest of the hardy.

Not far from the new town of Indian fighters was the Comanche Reserve, comprised of 70,000 acres along the Clear Fork of the Brazos River near the future town of Throckmorton. John R. Baylor, still smarting from his firing as Agent for the Penateka Comanches by his superior, Major Robert Neighbors, for allegedly misplacing funds meant to help the Indians, retaliated in spades by helping to establish "The White Man," published alternately in Jacksboro and Weatherford. The aptly named periodical presented the views of the frontier folk in the most direct terms. Baylor and his followers, whom he riled up with his partner H. A. Hamner's inflammatory rhetoric, were determined that the desirable land along the Clear Fork of the Brazos River was much too valuable for "savages" who had killed, scalped, and burned out too many whites along the frontier for the Indians to be permitted to live there. In the September 13, 1860, issue, of "The White Man," Hamner wrote, "The present condition of the frontier is truly alarming. The road is lined with movers from the different frontier counties, who have at last determined to quit the country and seek protection in the older states. For three years past the frontier people have begged, prayed, and supplicated both State and Federal governments for protection, and the Federal government has displayed a cold-blooded indifference to our condition that would do credit to the Czar of Russia."

Baylor led vigilantes to attack the reserve and threatened further attacks if the Comanches were not removed from their Texas Reservation. Neighbors. seeing that Baylor and his kind were not going to give up their efforts to rid the area of Indians, decided to move the Comanches north across Red River to the Wichita Agency near present Anadarko, Oklahoma. The Comanches might have left, but the hatred held by Baylor and his supporters towards Neighbors did not leave the Texas frontier with the Comanches. It lingered still in the heart of one of Baylor's and Hamner's followers. Believing in the need to remove the peace-loving Neighbors from the face of the earth, a coward unworthy of being named couldn't summon the courage to face Neighbors after the Major had returned to Belknap from taking the Comanches to the Wichita Agency in Indian Territory. Not surprisingly John R. Baylor's disciple shot Neighbors in the back with a shotgun, killing him instantly. Along with Neighbors went any hope for a peaceful existence between the Comanches and the Texans.

Fort Belknap, near present Graham, had been established four years before Jacksboro became a town as the northern-most outpost of army forts on the violent frontier. But with soldiers at the fort too far from the action in most cases, the Comanche and Kiowa warriors could strike outlying farms and ranches and be gone with captives, scalps and horses before the army could respond. Up to and during the civil war, in which many Jack County men fought as conscripts, the frontier receded by as much as one hundred miles in places. "The White Man" was widely read among the people who lived in the towns, ranches, and farms of Parker, Jack, Palo Pinto, Young, and Throckmorton Counties.

General Sherman came to Jack and surrounding counties in response to the Texans' constant calls for help in defending themselves and their families, especially in recovering the many children who had been kidnapped since hostilities first broke out between the Texans and the Comanches at Fort Parker in 1836, leading up to 1871, the year of General William T. Sherman's inspection of the frontier. Fort Richardson had been in existence for only four years, as a direct result of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the U.S. and the southern plains tribes in which a reservation was created for the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches. Fort Sill on the reservation and Fort Richardson just outside Jacksboro were both built to enforce the treaty by placing and keeping members of the three tribes on the reservation. The Indians could not legally leave what they considered to be a large outdoor prison without permission from the agent and/or the commandant at Fort Sill. These conditions were onerous in the extreme to members of the three tribes who were accustomed to moving around their formerly extensive hunting grounds with complete freedom.

In the summer of 1871, a Kiowa/Comanche war party left the confines of the reservation and headed south toward the Texas settlements for scalps and horses and, most of all, to avenge the many deaths among their people. The warriors positioned themselves in the trees and undergrowth on a hillside overlooking the road laid out by General Marcy in 1849. Marcy, Inspector General of the Army in 1871, accompanied General Sherman with a small escort of soldiers from Fort Belknap to Fort Richardson. Unknown to the two generals until later, they had passed beneath the hostile gaze of the Kiowas and Comanches but were not attacked because of the vision the night before seen by the Owl Prophet Mamanti of the Kiowas. His dream had foretold two groups of white men passing along the road below, and the second group was the one to be attacked. Thus, Sherman and his small escort was allowed to pass unmolested. Neither general knew how close he came to losing his hair on their inspection of the violent frontier until the war party returned to the reservation and Satanta boasted of their attack on the second group of white men, whose fresh scalps dangled from the scalp poles of the three Kiowa leaders.

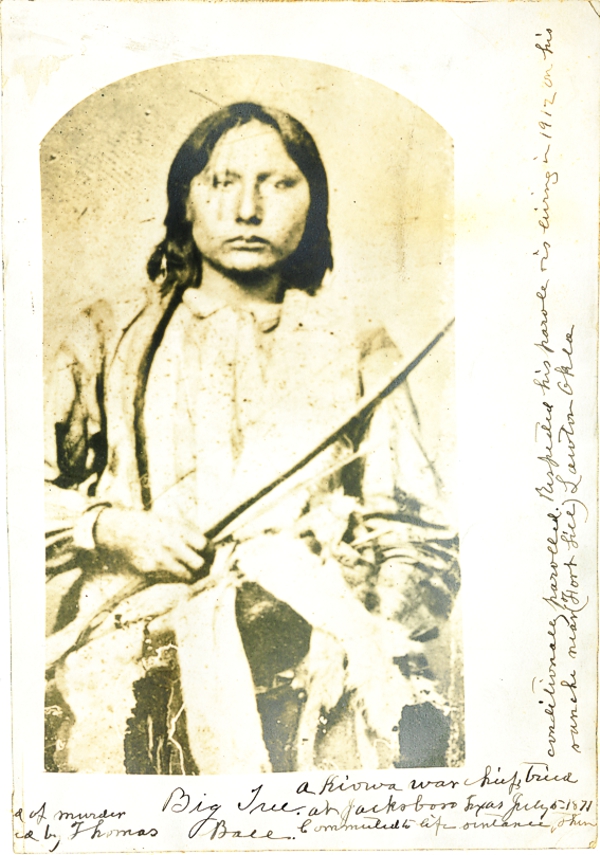

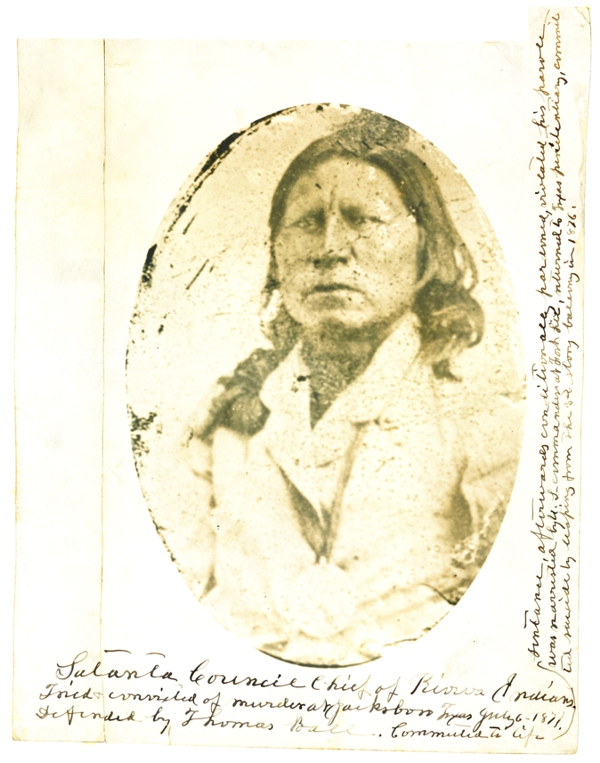

The second group of white men seen in Mamanti's dream, teamsters hauling goods on Warren's Wagon Train, suffered the most horrible deaths after fighting the attacking warriors until the twelve teamsters were overwhelmed, with only five escaping the horrible fate of their companions. Dying teamsters were tied to wagon wheels, tortured, and burned. Satanta, who had been one of the leaders of the assault on the teamsters, boasted in front of Quaker Indian Agent Lawrie Tatum, who was unarmed, of their role in leading the assault on the teamsters. But those would be the last scalps the three Kiowas would ever take. By bragging about the deed and showing their disdain for Lawrie Tatum, who was not a fighting man, the three chiefs angered General Sherman, who upon learning of his close escape from the Kiowas, was not in a peaceful frame of mind. Satanta, in fact, informed Sherman of his leadership on the raid. Rather than try the three Kiowas in a military court, Sherman ordered Colonel Ranald Mackenzie to take the three murderers to Jacksboro to be tried in civilian court. Satank, Sitting Bear in English, was shot and killed by Corporal John Charlton as the wagons were leaving Fort Sill on their journey south when Satank drew a knife from underneath his blanket and lunged at the men guarding him. Satank, singing his death song, landed in a sitting position, causing a creek nearby to be named Sitting Bear Creek after the brave Kiowa warrior who preferred death to imprisonment. The other two Kiowas, closely guarded, reached Jacksboro and were jailed, awaiting trial.

Satank had chosen death over facing the justice of a Jacksboro jury made up of cowboys from area ranches. The hardy men who sat in judgement of the two Kiowa chiefs had either lived in or around Jacksboro since its founding or were relatives or friends of the founders of the small town on the violent, blood-soaked frontier. The jurors were not among the whites described by Hamner in his plea for help in "The White Man" as having abandoned the country. To the contrary, the cowboys who held their ground and fought off Indian attacks were as tough as they come and may have known at least one or more of the victims of the Warren Wagon Train.

Perhaps one or more of the jurors had been witness to other massacres. Men from Jacksboro were probably part of the Texas force, led by Captain Sul Ross, composed of soldiers and Texas cowboys, in tracking down the Comanches who had killed a Mrs. Sherman, pregnant and close to giving birth, by shooting her abdomen full of arrows in one of the more horrifying examples of savagery on the frontier. The year was 1860, the same year of Hamner's call for armed support against Indian attacks, but the Comanche men who killed Mrs. Sherman in Parker County were not to suffer the consequences for their brutality. It would be Comanche women who paid the price. Chief scout Charles Goodnight whose ranch straddled the Jack and Parker County lines near present Perrin, led the collection of soldiers and volunteers along the trail left by the killers of the pregnant lady. They found Mrs. Sherman's Bible, a factor that fueled their anger even more. As they topped a small rise overlooking a tributary of Pease River west of Vernon, between present Crowell and Quanah, they made an even more dramatic discovery: the long-lost Cynthia Ann Parker, known to the Comanches as Naduah, Someone Found.

Only a sub-chief named Nobah and two or three younger men were present when Ross and his men attacked, shooting the fleeing Comanche women, who were preparing to lead horses and mules loaded down with bison hides and meat back to the village farther up Pease River between present Crowell and Paducah. Every Comanche woman except one, Naduah, was shot in the back. Only the cradleboard holding baby daughter Prairie Flower prevented Naduah's having been shot in the back as well. Naduah was returned against her will, after living for 24 years with the Comanches, to her white family in Weatherford. It is likely that Jacksboro cowboys were members of the militia, along with their neighbors from Parker and surrounding counties, who captured the female once known as Cynthia Ann, a name and identity she would reject during her eleven-year captivity with her Parker family relatives.

It is very likely that men of the jury at the Jacksboro trial of Big Tree and Satanta had lost friends and family members in the all-out war that had been raging between Texans and Comanches since Cynthia Ann's capture at the age of nine in the Comanche, Kiowa, and Wichita attack on Fort Parker in 1836. In any case, the jurors sentenced Big Tree and Satanta to death, a sentence later commuted by the governor of Texas upon the urging of President Ulysses Grant, who feared an Indian uprising if the Kiowas were executed or imprisoned for life. After being released on parole, Big Tree returned to the reservation and remained peaceful. Satanta, however, rode with the Plains Indians who attacked the buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle in the summer of 1874. As a result, Santanta was arrested and returned to prison. In despair, Satanta followed Satank's example and sought death by leaping to his death from an upper story window of the Texas prison in which he was incarcerated.

John Wood was the author's great-great-grandfather. His granddaughter, Emma, (the author's grandmother), born one year after the trial of the Kiowa chiefs, attended a country school about fifteen miles southwest of Jacksboro, probably Oak Grove School, the one attended by her daughter and son, Myrtle and the author's father Luther Neeley. After Emma completed school in Jack County, John Wood sent his granddaughter to Weatherford College, established in 1869, about 1890. There she met Frederick Plummer Neeley from Iola, Texas, located just to the south of present College Station, whom she later married. The newly-weds settled down on John Wood's ranch just to the west of Perrin not far from the ranch of Charles Goodnight and made Jack County their home for the next several years.

As one of the hardy pioneers who refused to leave his ranch, John Wood endeared himself to the people of Jack County. His obituary in 1902 reflects the esteem in which he was held. "John Wood of Salt Hill, the oldest citizen of Jack County, died Tuesday at his home where he settled in 1855. Mr. Wood was here through the Indian troubles from 1859 to 1872. He was an honored and highly respected citizen and universal sorrow is felt at his death."

Jacksboro's roots reach deep into the soil of the land that shaped the people who live there today, yet many now enjoying the fruits of peace may not know that those who once lived in Jack County sacrificed so that their descendants could enjoy the life they currently lead in a land once dominated by cowboys, soldiers, and Indians.

Bill Neeley Neeley Books